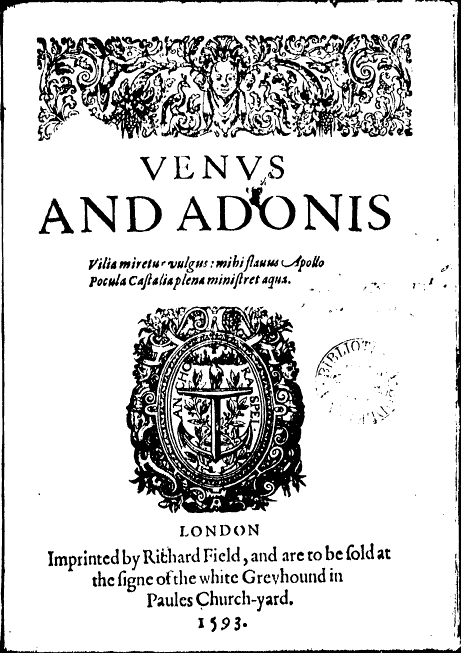

An actor's impression of Venus and Adonis

SAT Trustee and actress Annabel Leventon shares her first encounter with Venus and Adonis

It’s annual gathering and conference season. The De Vere Society’s conference held on 12 October was on Hermeticism, a subject I knew nothing about, and it was so enlightening and satisfying I felt my life had changed.

I’m looking forward to my second Shakespearean Authorship Trust conference on 17 November. We will be looking at the connections between the long poems and their dedicatee, the Earl of Southampton, equally a subject I know little about. I’m looking forward to learning about the connections between the two. It’s a privilege to take part in these meetings with well-informed people who know so much.

As an actor, I’ve lived with Shakespeare’s plays all my life, but it was a while before I read his long poems. In the first of them, Venus and Adonis (1593), Venus, Goddess of Love, lusts after Adonis, a beautiful youth who is more interested in hunting than affairs of the heart. He escapes Venus’s clutches, gets gored by a wild boar, and dies.

Margo Anderson tells us that “Venus and Adonis fast became a best seller. The esoteric levels of meaning may have been lost on many readers, but the buzz the poem created was still enough to keep it flying off the shelves, generating an average of one new printing a year in its first decade.”

To my amazement, I thought the poem was close to pornography. I could see how it became so popular. Here’s a sample:

“Fondling,” she saith, “since I have hemm’d thee here

Within the circuit of this ivory pale,

I'll be a park, and thou shalt be my deer;

Feed where thou wilt, on mountain or in dale:

Graze on my lips; and if those hills be dry,

Stray lower, where the pleasant fountains lie.

Within this limit is relief enough,

Sweet bottom-grass and high delightful plain,

Round rising hillocks, brakes obscure and rough,

To shelter thee from tempest and from rain.

Then be my deer, since I am such a park;

No dog shall rouse thee, though a thousand bark.”

Putting the story into such racy language must have been startling enough to a Tudor audience. But it seems to go much further. Venus might be standing in for Queen Elizabeth herself. The references to her, with the constant mention of red and white (the Tudor colours), her age, power, waning beauty, and rapacious desires, were pretty obvious and a searingly offensive portrayal of a sixty-year-old woman desperate for a younger man’s love, if true.

This was the first publication to credit William Shakespeare as author. It would have been a punishable offence, if it were proved he was referring to the Queen. Nobody was ever charged.

However, it didn’t go unnoticed. One Londoner, William Reynolds, wrote to Burghley in the summer of 1593: “Also within these few days, there is another book made of Venus and Adonis, wherein the queen represents the person of Venus—which queen is in great love (forsooth) with Adonis. And she greatly desires to kiss him. And she woos him most entirely, telling him that although she be old, yet she is lusty fresh and moist and full of life. I believe a good deal more than a bushel-full. And she can trip it as lightly as a fairy nymph upon the sands. And her footsteps not seen, and much ado with red and white.”

The response was swift: “William Reynolds’s most impudent, abusive, and nearly treasonable letter to the Queen; with two others to the Lords of the Council, and to the Citizens of London; reviling them all in most scurrilous terms, such as only absolute madness can excuse.” (British Library)

Reynolds was declared insane.

In 1992, then British poet Laureate, Ted Hughes, published Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, interpreting Venus and Adonis as a key to Shakespeare’s tragic dramas. Alice Oswald will be sharing her thoughts on this at our conference.

I hope to learn much more on November 17th.